Maurice Gover

6 November 1827 – 7 June 1908

Ten miles down the road from Bristol, England is the village of Clutton.

At the dawn of the 19th Century it consisted of one hundred and

seventy five houses and nine hundred inhabitants. Situated on very

high ground, the country abounds with coal. There are also extensive

quarries of stone for paving and building, and of limestone, and

several kilns for burning lime; and iron-ore was found in the

coal-mines and in other places. The majority of the population was

employed in the coal mines. Coal had been mined in North Somerset and

the Bristol region for many centuries, and was possibly being mined

in the region during Roman times. Clutton had three pits belonging to

the Earl of Warwick's estate, which owned all the land in the parish

of Clutton.

Charles Gover was at least the third generation of the Gover family which had lived in Clutton dating back to 1719. Charles was born on July 20, 1802. When he was about twenty one or twenty two years old, he married Ann Day who was also born in Clutton on May 24, 1801. The Days were from Congresbury, twenty miles west of Clutton.

Maurice Gover was born November 6, 1827 in Clutton, Somersetshire, England. (Family and other records show Maurice's birth-year as 1827. But his headstone and the Endowment House Records show the birth-year as 1828.) Maurice's was the second of six children. His brother and sisters were: Mary Ann (28 Nov 1824), Rose (1830 – 1841) , Martha (17 Aug 1834), Charlotte 17 Sept 1837), Emma (4 Nov 1841), and Robert (19 Dec 1845). Maurice began working in the coal mines at a very early age. As a young man, he enlisted as a soldier in the English Army, but his parents paid for his release.

Also living in Clutton was the family of William and Martha Rogers Tucker who where the parents of eight children. Their oldest daughter, Sarah was born on July 14, 1827. Maurice and Sarah were married in the Clutton Parish on June 11, 1848.

After centuries of mining, the coal mines around Clutton began to be depleted and there wasn't as much work. What was a stonecutter to do, but move on to where there was more work. Soon after they were married, Maurice and Sarah moved about fifty miles away to Abersychan, Monmouthshire in South Wales. It was there that their first child, Emily, was born on June 18, 1849. They were happy and comfortable as he did well financially. They had a nice home and were quite contented when the gospel message was brought to them by Elder Cooke. Morris was interested and began investigating immediately.

The seeds of the gospel took deep root in his soul. His wife was not so readily impressed. She said they were happy and contented, and she was very satisfied before the Elders made such an impression upon her husband. She felt confused about the Mormons. Nevertheless they joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Morris was baptized on April 10, 1849 by John Price and confirmed by Edward Prothern. Christopher Author ordained him a priest in May 1849 and an Elder in 1852. Simon Smith ordained him a High Priest. Morris baptized Sarah on September 10, 1849. He was firm in the faith and made his home a home for the Elders. He went about as a Block Elder preaching the gospel and after returning home Sarah would often find his clothes splattered with rotten eggs.

After they joined the church, it was hard to secure work. Most of the employers were antagonistic against the Mormons. While living in Wales, he found employment until he could save enough to come to America. Both of their parents were opposed to them going to America. Sarah's mother, Martha Rogers Tucker, told Sarah to tell him that she didn't want to go. If she would be determined not to go to America, then Morris would not go without her. When she asked him about it he said, "It is my desire to take you with me, but if you will not go then I shall go alone." Sarah said, "I knew he meant it."

Just before leaving for America, their son, Elijah was born on January 22, 1853 in Abersychan. Elijah was one month old when they boarded the International. While waiting for the wind to take them out to sea, he died the night before the ship was to sail. Maurice got permission to leave the ship and took the little child's body to some farmers he found in a field in Kea Cot, England, and gave them some money to bury the baby. They always felt comforted that he was buried on land, instead of at sea. Saddened, Maurice, Sarah, and four year old Emily pressed on.

The square-rigged International weighed 1,003 tons, and was 176 feet

long. This particular voyage was one of the most successful and

notable Mormon emigrant voyages. It began at Liverpool on February

26, 1853. On board were four hundred twenty five Saints under the

presidency of Elder Christopher Arthur and his counselors, John Lyon

and Richard Waddington. Captain David Brown of Provincetown,

Massachusetts, was part owner and master of the vessel. During the

crossing there were seven deaths, seven births, and five marriages.

Elijah's death was recorded in the captains log before setting sail.

The 1,003-ton ship International was built at Kennebunk, Main in 1851.

Registered in Boston by George Lord, the 175 foot vessel sailed as a

regular transatlantic trader and sometimes immigrants – like the 425

Mormons sher carried in the spring of 1853 – were all likely westbound

“cargo” for a ship like this. In 1861, William York of Liverpool painted

the International laboring in a full gale. Her main lower topsail is

holding, but the fore-topmast staysail and main spenser have burst

with the force of the wind, and the furled crossjack is blowing to pieces.

Though encounters seven years later, these trying circumstances were

reminiscent of he 1853 passage with the Latter-day Saints.

(Mystic Seaport, 67.75)

Shortly after the ship left port, Elder Arthur called a meeting of priesthood holders in the company. He then divided the emigrants into eight wards, six for the steerage and two for the second-class cabin passengers. An elder presided over each ward and was accountable to a general council. These leaders were responsible for the health, behavior, and welfare of the emigrants. Every evening, meetings were held for worship, instruction, and testimony bearing.

The passengers drew their rations, consisting of hardtack, rice, tea, sugar, salt, beef or pork once a week. They were given four quarts of water each day and had to get it early in the morning. As soon as they were organized they commenced a routine, which was about as follows: up at daylight and get breakfast. Then came morning prayers in all the wards, then it was sweep and clean up. After that they could promenade on deck, sing, or do whatever we chose until time to have dinner.

The cooking was done by two young men in a little house on deck called

the galley. In the morning they would have two big boilers of hot

water and those who wished tea, would take some of their cold water

and exchange it for some hot water. The meat was all boiled together,

each person tying a wooden or tin tag with his name or the number of

his berth on it to his piece. Rice was tied in a bag and cooked the

same way. If a person wanted anything fried or cooked in any other

way, they would have to wait their turn. Most of the passengers took

fresh meat, fresh bread, butter and many other things with them, so

that they didn't suffer for anything to eat.

Maurice Gover

For five weeks the ship encountered strong headwinds and heavy gales that slowed their progress. In one storm the vessel nearly capsized. After five weeks at sea, the Captain declared that if he were to turn the ship around they could be back in Liverpool in just ten days. Elder Arthur called a meeting and explained the situation and asked the Saints to fast and pray for a fair wind, which they did the following day. That afternoon at four o'clock the wind changed.

During the voyage the Saints were filled with religious fervor, and spiritual manifestations such as speaking in tongues and prophesying were reported. In a letter to President Samuel W. Richards, dated 26 April 1853, Elder Arthur described a unique missionary success:

"These things and the good conduct of the Saints have had a happy result in bringing many to the knowledge of the truth. And I am now glad to inform you that we baptized all on board except three persons. We can number the captain, first and second mates, with eighteen of the crew ... The others baptized were friends of the brethren. The number baptized in all is forty-eight ... The captain is truly a noble, generous-hearted man; and to his honor I can say that no man ever left Liverpool with a company of Saints more beloved by them, or who has been more friendly and social than he has been with us; indeed, words are inadequate to express the fatherly care over us as a people; our welfare seemed to be near to his heart."

On the 6th April the emigrants assembled on the forecastle to celebrate

the twenty-third anniversary of the organization of the church. Six

musket rounds were fired and the festivities began. The celebrants

marched to the poop deck, and the leaders robed in sashes with white

rosettes on their chests, took their seats with their backs to the

mainmast. Twelve young men and twelve young women, picturesquely

robed, seated themselves on each side of the presidency. Then there

were scripture readings, partaking of the sacrament, speeches,

singing, recitations, dancing, and four marriages. The program lasted

until late at night. President Arthur wrote: "everything was

done with the highest decorum."

Sarah Tucker Gover

This happy voyage ended at New Orleans on April 23rd – a fifty four day passage. The captain said that he had never sailed the same distance covered during the last three weeks of the voyage so fast, at times sailing about two hundred twenty miles a day. Except for minor bouts of seasickness, the emigrants were remarkably free from illness.

After landing in New Orleans, they sailed up the Mississippi River on a steamboat for 1,000 miles to Keokuk, Iowa. From there, they crossed the plains to Salt Lake City with one of the church teams, the Jacob Gates' company. This company was part of the Perpetual Immigration Fund that was provided for those coming across the plains that did not have any other means. Those who came this way reimbursed the church later. The company they came in consisted of two hundred sixty-two people, thirty-three wagons, one hundred forty-seven oxen, forty-seven cows, two mares, one bull, three lambs, and five dogs.

While crossing the plains it was necessary to go through many streams and rivers. The men would tie ropes around their waists and swim to help pull the wagons. After one of these exhausting experiences, Maurice came down with a severe cold and had what was then called ague fever. Ague fever is a combination of chills, fever, and sweating recurring in regular intervals. As a result, he had to ride the rest of the way and he never did completely recover from this illness. His illness left Sarah to care for Emily, gather firewood, and do all of the work in camp that each family was expected to do.

When the company started out, the food supplies were stored together, but when they were getting low the food was divided out among the families. When they arrived in Salt Lake City on September 30, 1853 Maurice and Sarah had one quart of flour left. They slept in a wagon box that night and the next day Sarah began working at a home where her pay was their board.

Upon arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, the Gover's lived in the Tenth Ward and later moved to the Nineteenth Ward in Salt Lake City. Maurice was a guard over the home of President Young for a little while after arriving in Utah. That winter he worked on the railroad. Once in the Salt Lake Valley, many of the saints would be re-baptized, although unnecessary, as a sign of recommitment to the gospel. Maurice was re-baptized by Martin Harris and confirmed by Simon Smith.

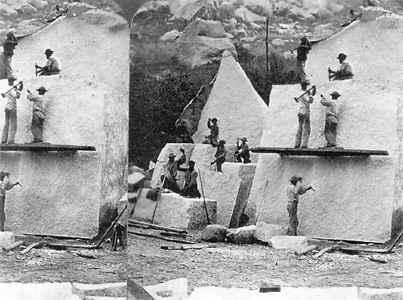

Maurice, a trained stonecutter, and worked in the rock quarry for sixteen years where

the granite for the Salt Lake Temple came from. He said every stone

was numbered so, if necessary, the temple could be disassembled and

re-erected exactly the same. He would leave home on Monday morning

and not return until Saturday night. For his pay, he received some

money and the rest in food supplies for the family. Sarah would go to

the tithing office and stand in line, sometimes all day for her turn

to get supplies.

The granite quarry in Little Cottonwoood canyon

While living in Salt Lake City, six more children were born. Lydia (November 24, 1854), Henry Morris (December 20, 1857), Martha Ann (March 24, 1860), Sarah, who went by Sadie (February 8, 1862), Emma (November 19, 1864), and Rosena (June 3, 1868). Emily, married George Godfrey on November 26, 1865 and established a home of her own. She was not yet seventeen when they were married.

Maurice and Sarah's marriage was solemnized in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City, Utah on September 25, 1855 by Brigham Young and witnessed by Heber C. Kimball and Jedediah M. Grant. His marriage record from Clutton Parish, the emigration records by ship, and the early church records of Salt Lake City and Clarkston wards, as well as the citizenship records give his name as Maurice. At some point he changed his name to Morris sometime after moving to Utah.

The family moved to Newton, Cache County, Utah in about 1869. They lived

there a short time and then moved to Clarkston. There, they bought a

farm with a one-room log house and a wagon with a team of horses for

their son's employment, since Morris had no interest in farming. The

log house did not have a ceiling in it, only the rafters and a dirt

roof. The home was located on the southwest comer of the city lot,

North block; number three. There was a spring nearby and they carried

water for all of their needs. Their beds were made of four blocks of

wood, cut from a large log for the legs and a wooden frame built on

top of them. Ropes were laced back and forth for springs.

The Gover home in Clarkston.

This frame house was built later on the same parcel as the log house.

Before long, Morris had a new home built on the same parcel as the one room log cabin.

Not long after moving to Clarkston, Morris received a letter from his brother, Robert, telling him that he had also immigrated to America and was living in Chicago and that their sister, Martha had immigrated to Canada.. Robert also informed him of the deaths of their parents. (Robert eventually settled in Marquette, Michigan and Martha later moved from Montreal to Buffalo, New York.)

Mule drawn freight wagons used to pass through Clarkston on their way

north into Idaho and Montana. These freight wagons brought tragedy to

the Gover family. Henry, and some of his friends were sampling the

the freighters beer by putting hollow wheat straws into the kegs.

Henry got some of the foam from the top of the keg. Cobalt, which is

a heavy metal, used to be added to beer to stabilize the foam, but

it can be poisonousness under before the foam evaporates. This caused

his death on May 25, 1875 at the age of eighteen. After Henry died,

Morris sold the farm. That was not a good year for the Gover family.

They family came down with diphtheria and Sadie, who was fourteen,

died from the disease on September 21, 1875.

Henry Morris Gover

Morris received his Certificate of Citizenship on September 8, 1882.

As their surviving daughters grew up, one by one they each married and established homes of their own. Lydia married John Ezekiel Godfrey on November 24, 1873. John was the brother of Emily's husband, George. Martha Ann married Thomas Griffin on June 12, 1876. Emma married Daniel Buttars on December 27, 1883. Rosena married John Edward Godfrey on December 2, 1891. (John was a cousin of George and John Ezekiel Godfrey.) In the meantime, Emily died from complication in childbirth on November 26, 1881.

When Morris would sort the potatoes from his garden, he would pick out the

largest ones and put them in a separate container, these were his

tithing. He would do the same thing each time he gathered his eggs.

The eggs were put on the table; he would pick out the largest and set

them aside in a dish. The rest went into the egg basket. Each Monday

afternoon Sarah would take them to the store where she would get a

tithing receipt. The storekeeper, Thomas Griffin, would sell the

potatoes and eggs, and then turn the money over to the Bishop.

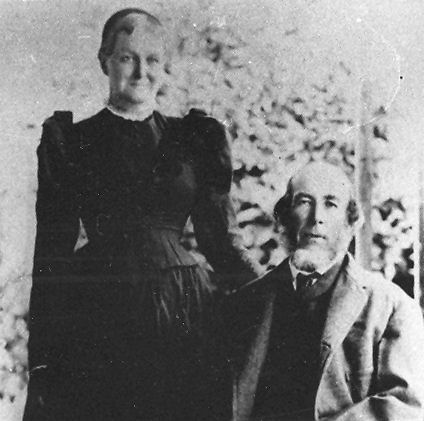

Sarah Tucker and Morris Gover

Morris was extremely neat. Many accounts tell how he prided himself that he could find any tool on the darkest night without a light, because he had a place for everything and kept things extremely orderly. He was also very particular about his yard which was weed free except for the few pigweeds he allowed to grow so he could feed them to his pigs. One day when he went to the well to draw some water and he found a frog in it, so he dug a new well. Morris and Sarah kept a rag carpet on the path from the house to the well, which was swept every day.

Morris always struggled with poor health after getting sick while crossing the plains. Often he laid on the floor, saying that was the only place he was comfortable. He always said that he didn't want to die in bed, and didn't. When they found him, he was on the floor, and had died with his boots on. He got his wish not to die in bed. Morris Gover died in Clarkston, Cache, Utah, on June 7, 1908 at the age of eighty years old.

Sarah lived for few more years and died in Clarkston, February 15, 1917 at the home of her daughter Emma Gover Buttars at the age eighty-nine years old. They are both buried in the Clarkston cemetery, block #6; Lot #6, place #1 &2.

Morris and Sarah had forty six grandchildren, seven of which died as babies or small children. With the death of both of their sons, there was no one to pass along the Gover name. However, Emma did name one of her sons Gover and it was a middle name for a few grandchildren and great grandchildren.

The main source for this biography was the “Life Story of Maurice Gover and Sarah Tucker” written by Archulious B. Archibald and other family histories.